This article was originally published by the Cap Times on Nov. 6, 2017.

Recently, a colleague asked me about whether there was a difference between reading a book on a screen versus a paper page. People do worry about all sorts of concerns — light from screens, fine motor skill development, reading comprehension, and more. Many of these stem from an underlying technophobia — or technophilia, as it may be. What does the research tell us?

There are published studies which formally examine the difference, and the results seem to be all over the place. Some suffer from small sample sizes, or look only at very specific domains — comprehension, or interactional parent/child “warmth”, or mastery of a specific skill. There’s also a big difference looking at toddlers versus preschoolers versus elementary schoolchildren; they are at very different places in the world of reading. Additionally, many are adult studies, and may not apply to children. The reality is that, based on the available research, we just don’t yet know if there are significant meaningful differences.

I’m asked this question frequently when I give talks about early literacy, and I try to give at least some amount of guidance. My answer is as follows: To a certain extent, I think that text is text, whether it’s being viewed as ink on the dried wood pulp that we call pages or glowing pixels on a screen. There are a few key caveats, though:

First, the research is mixed on whether use of backlit screens can impact sleep. Melatonin is a hormone involved in initiation of sleep, and it is affected by light exposure, particularly certain wavelengths. While television has been in our collective lives for decades, those screens are a few feet away, rather than the several inches of most portable devices. However, while studies of close-in light use may affect melatonin, does typical real-world use do so? It’s hard to know as of yet. Until there’s better clarity on this, avoiding glowing screens at least an hour before bedtime is reasonable.

Second, most books for young children involve skillfully created images. Ensuring a screen is high-quality enough to allow the beauty of the images to be displayed is important and shouldn’t be compromised. Illustrations are as much part of the story as the text.

Third, there is a danger of a slippery slope when it comes to electronic devices — even young children often know devices can not only provide a Caldecott-award-winning picture book, but also offer up games. It’s hard for parents to resist a young child’s demands for the attention-grabbing nature of games — after all, marketing cereals to children is predicated on them throwing tantrums in the supermarket for a particular kind — with a high risk of displacing the intention to share books together…night after night.

Finally, there’s the danger of thinking the enhancements offered by e-books are necessarily an improvement over physical books. A parent might assume having a cow moo when tapped on a screen is inherently better than the silent paper equivalent. But is it? If that moo is not essential to the narrative or structure of the book, it may simply be a distractor. Children who become attuned to the “tap-and-make-something-happen” dynamic may ignore much of what is on displayed pages in favor of tapping everything on the screen in an attempt to “make it go”.

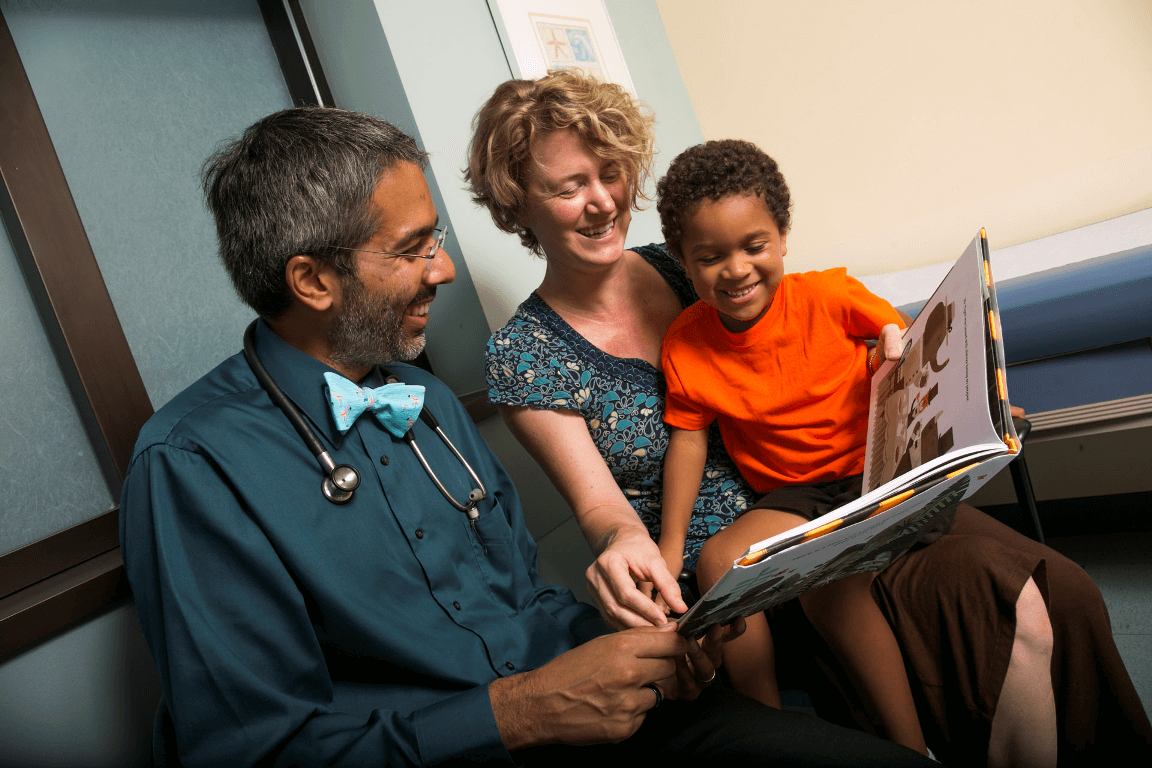

Ultimately, it all comes down to how the book is used. Assuming due care is exercised with the above points, for young children the most important factor is the presence of a caring, nurturing, responsive adult who understands how to interactively explore a book with a young child. This may be a skill unconsciously picked up by the adult through environmental role models, but for some they may require modeling, coaching, and the encouragement to do so. Rather than become lost in the electronic versus paper book wars, we would do well to ensure that each and every child has an adult in their lives who knows how to read well with them and can do so routinely.

Very nicely said, Dipesh. Thanks.

Thanks for clarifying the relationship between melatonin and light exposure from a close-in screen! I need to end that bad habit!

And your bottom line is one Wisconsin Literacy is really trying to support:

“to ensure that each and every child has an adult in their lives who knows how to read well with them and can do so routinely.” Thanks Dipesh!

Michele Erikson

Wisconsin Literacy, Inc.